|

So. Anything new happen while I was gone? LOL.

I've had major personal blog writer's block. I was busy processing all the COVID/US election + insurrection/climate change stuff, and also writing a lot for work. Plus, washing groceries takes a lot of time. ;) Where does one even begin? I guess with 5 things I've learned in the After Times – at least the things I can identify to date.

1 Comment

We have a new nest. It's in St. Petersburg, and it has a pool, which is a huge luxury. It was built in 1940 and is in Historic Kenwood, which we love. Our new hood is artsy and progressive. We have a brick street. I always wanted to live on a brick street. It also has an annex, aka the studio. The annex is perfect for guests and daughters who are now away at college. We are also near some really excellent friends. We moved so my husband wouldn't have to commute 10 hours a week. We're still very near family, and we like this city.

I love that the hilarious, colorful Freddie Webb wrote this about herself, for her own obituary. And I also love that Dunedin, Florida, residents organized a golf cart parade in her honor, a couple weeks after she died on June 27.

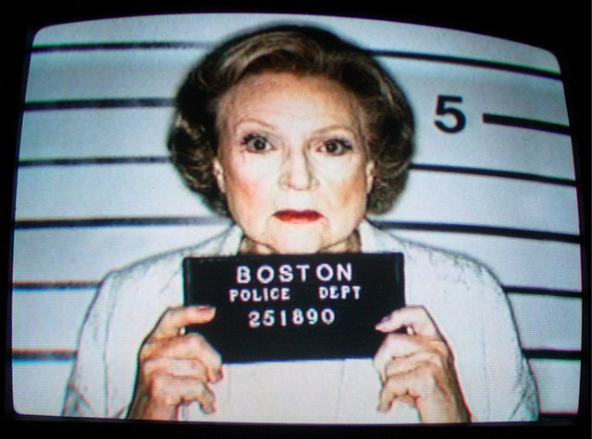

I recently watched If You're Not in the Obit, Eat Breakfast on HBO. It's about a group of famous nonagenarians, and it examines whether you can still enjoy yourself at that late life stage. The documentary interviewed such well-knowns such as Carl Reiner, Mel Brooks, Betty White and Dick Van Dyke. The latter, besides being a bit of a cornball, is a wonder — the man moves like he's 35. And that's what he says is vital to enjoy your 90s: keep moving, and use your brain. (Meanwhile, Betty White is writing books like a demon.)

I would make a terrible police witness. If I witnessed a crime and had to testify, I would have to write the victim a profuse apology note for my crap observational skills. As I previously mentioned in an earlier blog, I need to pay a lot more attention to what's going on around me. See, I have a tendency to live in my head. I have lengthy dialogues in there, as I suspect many people do, and sometimes, I'll even repeat those conversations out loud. In other words, I talk to myself a lot.  Creative Commons: orangeacid Creative Commons: orangeacid "I'm no good at math." I must have heard this come out of my daughter's mouth a thousand times over the years. When she was in primary school, she would hide behind the curtains and cry when it came time to review her math homework. She hated it so much, and there was no convincing her otherwise.

Do you remember this 1970s Crackerjack TV ad? (If you don't, then just watch it. That's why I embedded it. You're welcome.) "Whaddaya call a kid who can swing like that? You call that kid a Crackerjack."

This ad popped up repeatedly during Saturday morning cartoons when I was a kid, and jealousy would surface. I would bitterly think, "What's wrong with me? How come I'm not really good at any one thing? I'm not a Crackerjack kid." I certainly wasn't that girl in the ad: I took gymnastics, and while I managed to learn how to do an aerial, I never could master a back handspring or the uneven bars because my arms were too skinny and weak.  Fire of the Notre Dame Cathedral seen from Saint-Louis Island, Bourbon Quay, 8:38 p.m. Paris local time. 4/15/2019 (Cangadoba / Wikimedia Commons / CC Share Alike 4.0 International) Fire of the Notre Dame Cathedral seen from Saint-Louis Island, Bourbon Quay, 8:38 p.m. Paris local time. 4/15/2019 (Cangadoba / Wikimedia Commons / CC Share Alike 4.0 International) My BBC iPhone notification pinged. Notre Dame was on fire. Cue nauseous feeling, like when the Glasgow College of Art caught on fire - twice. Go to Twitter, look at photos of the flames shooting out of the roof. Burst into tears when the spire falls, and sob for a half hour. Yell, "No!, No!, No!" at my phone. I look at Slack, to see how my Fast Company colleagues in New York and San Francisco are scrambling to cover this horror with our unique angle. (I work from Florida. That's another story for another day.) Of course we need expert input, so architects/engineers/construction experts are discussed. I suggest my husband. (Hey Scott, who asked the headline question on Facebook: this is how it happened.) |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed